Understanding the "Paganism" of the ENR - Part 1

In a compelling dialogue with Thomas Molnar, French philosopher Alain de Benoist argues that Biblical monotheism set in motion the West's gradual departure from authentic sacred experience.

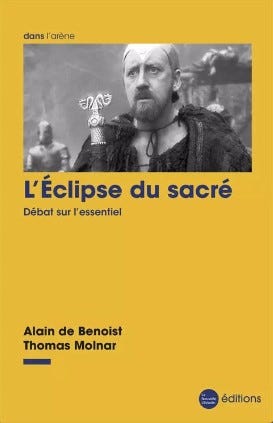

The book, L'Eclipse du sacré (The Eclipse of the Sacred), is a dialogue between Thomas Molnar and Alain de Benoist about the nature of the sacred and its decline in the modern Western world. Molnar defends Christianity and argues it enriched rather than diminished the sacred. De Benoist argues that Biblical monotheism initiated a process of desacralization that led to modern secularism and the "death of God.” In order to gain a better understanding of the “paganism” of the European New Right, I have summarized the arguments made by Alain de Benoist in this dialogue between him and Thomas Molnar.

De Benoist argues that the desacralization of the modern world can be traced directly to the advent of Biblical monotheism and its unique conception of the relationship between God, humanity, and the world. His analysis centers on how Judeo-Christian thought initiated a series of fundamental ruptures that eventually led to our current secular age.

The first and most crucial rupture was the radical separation between God and the world. Unlike in pagan traditions, where divine forces were seen as immanent within nature and the cosmos, the Biblical God stands entirely outside His creation. This transcendent monotheism emptied the natural world of its sacred character - nature became merely created matter, an object to be dominated by humans who were commanded by God to "subdue the earth." This initial dissociation spawned all subsequent dissociations: between spirit and matter, soul and body, faith and reason.

For de Benoist, the pagan sacred was fundamentally different. In Indo-European traditions, the sacred (sacer) was what manifested the presence of divine forces within the world itself. It functioned as a mediator between the visible and invisible realms, between humans and gods, earth and heaven. The sacred wasn't identified with the divine but rather emerged at the intersection point where these realms met. Importantly, there was no unbridgeable ontological gap between humans and gods - they belonged to the same being, though at different levels.

This pagan conception allowed for a genuine experience of the sacred through ritual and sacrifice, which periodically recreated cosmic order by bringing the human and divine into communion. The sacred was thus deeply tied to particular places, times, and communities. It was both transcendent and immanent, universal in principle but always manifesting in specific forms.

Christianity, by contrast, reduced all sacred mediation to the single event of the Incarnation. While this didn't immediately eliminate traditional sacred practices (which the Church had to accommodate), it laid the groundwork for their eventual dissolution. If God is radically other than the world, and Christ is the sole mediator between God and man, then all other forms of sacred mediation become ultimately dispensable.

De Benoist argues that Christian rationalism emerged from this same source. By identifying God with Being itself and making Him the ultimate cause of all that exists, Christianity subjected everything to the principle of reason. The world became an object of rational investigation rather than sacred contemplation. While the Church often opposed scientific inquiry, its own theological premises - particularly after their systematization by Scholasticism - helped create the intellectual conditions for modern rationalism and science.

Similarly, Christian individualism, with its emphasis on personal salvation and the unique worth of each soul before God, helped birth modern liberal individualism. The universal equality of souls before God became, in secularized form, the universal equality of rights-bearing individuals. Christianity's ethical monotheism, which placed supreme importance on the relationship to the other rather than the relationship to the world, evolved into secular human rights discourse.

Thus for de Benoist, secularization represents not so much a break with Christianity as its logical culmination. Modern atheism emerged from Christian monotheism like a child eventually rebelling against its parent. The "death of God" proclaimed by Nietzsche was prepared by centuries of Christian theology. Today's secular West remains profoundly Christian in its basic structures of thought, even as explicit Christian belief declines.

De Benoist sees this process as fundamentally tragic. The disappearance of authentic sacred experience has left modern humans spiritually impoverished, cut off from both nature and genuine community. Various attempts at "re-enchantment" - whether through new age spiritualities or political religions - cannot fill this void because they remain within the individualistic, rationalistic framework inherited from Christianity.

However, de Benoist doesn't simply advocate a return to paganism. Rather, he suggests we need a new understanding of the sacred appropriate to our time, one that would restore humanity's connection to both nature and the divine without falling into either primitive superstition or abstract monotheism. He finds resources for this in certain philosophical traditions (particularly Heidegger's thought) and in new scientific paradigms that challenge mechanical materialism.

The sacred, for de Benoist, remains always possible because it is rooted in the very structure of human experience of the world. What's needed is not so much a "return" to ancient forms as a reawakening of this fundamental human capacity for sacred experience. This would involve recovering what Heidegger called "poetic dwelling" - a way of being in the world that remains open to mystery and transcendence while remaining grounded in the concrete reality of place and community.

De Benoist thus presents a profound critique of both Christian theology and modern secularism, arguing that they represent two phases of the same historical movement away from authentic sacred experience. His analysis suggests that addressing our current spiritual crisis requires going beyond both traditional monotheism and secular rationalism to rediscover a more primordial relationship with the sacred.

Okay, so I read the article again, for greater clarity. (I still struggle with all of these new ideas). But I appreciate the summary of de Benoist's thought on the problem of Christianity. It's extremely intellectually stimulating. Well done!

Ican see why someone would level this type of criticism against the institutional Church. Funnily enough, I think Christ would say much the same thing. Listen to Him outside of the strict parameters of the institutional Church, in His own voice, His authentic, authoritative voice, and He blasts the Pharisees/hierophants much along the same lines. They drove an iron wedge between the Creation and the Creator, and drained the spiritual significance from the natural world, so that all that left was an empty, material husk. Jesus promised that He would revive and restore the created order.

But the true Church is not false, it's authentic man, in a new and revived state.

Interesting. I'm not sure I agree, though, with the thesis that Christianity entirely and completely desacralized the world. I would make some caveats. Christianity isn't monolithic -- there are two major branches: the Greek East and the Latin West. The Latin West is then further divided into the Roman, Anglican, Lutheran, and Reformed and Presbyterian, and so on. Each of these branches had their own doctrine on nature, some more desacralizing then others. It was branches of Western philosophy that exerted a far worse effect on the natural world. The materialists and empiricists of the Enlightenment saw the world as matter, strictly. They stripped nature of its power! Blame them! It's how closely did a Christian branch embrace that philosophy that counts.