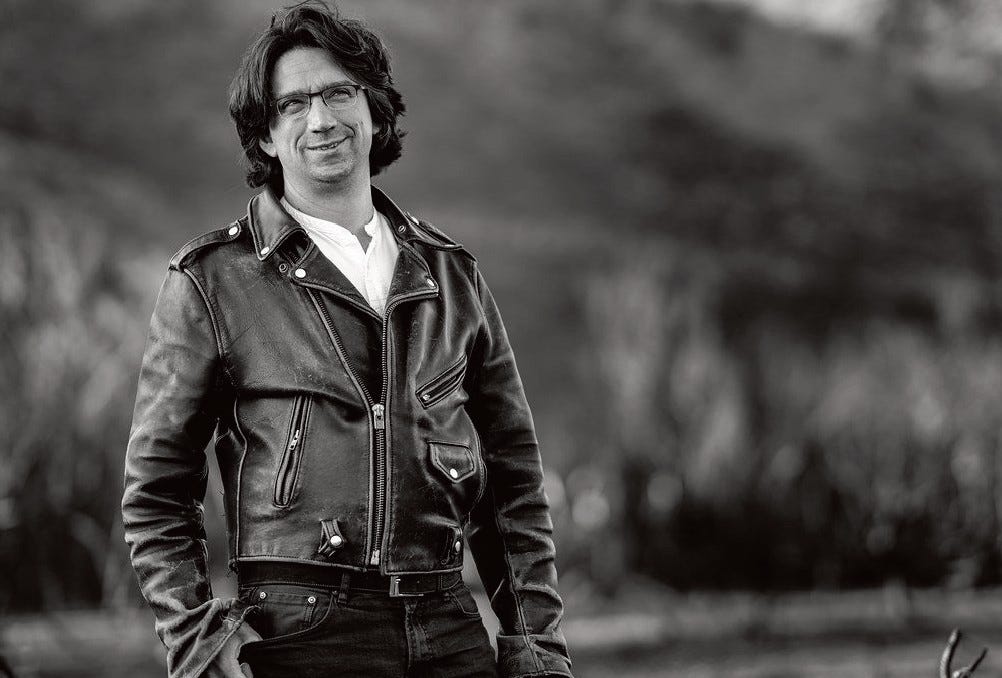

Meeting with the Father of Neoreaction

Curtis Yarvin: “Progressivism Irresistibly Tends Toward Chaos”

Curtis Yarvin, known both for his pseudonym Mencius Moldbug and his role as the intellectual architect of the neoreactionary movement (NRx), is a thinker who thrives on challenging modern assumptions. In this conversation, he dissects the hidden mechanisms of power, critiques the illusions of democracy, and explores the unintended consequences of Enlightenment ideals. From his concept of the "Cathedral"—a decentralized system of ideological control—to the future of governance in an age of technological upheaval, Yarvin lays out a vision that is as unsettling as it is thought-provoking. Whether one sees him as a visionary or a heretic, his ideas demand attention.

Originally published in Éléments no. 212, February-March 2025.

Translated by Alexander Raynor

An iconoclastic thinker and father of the neoreactionary (NRx) movement, American Curtis Yarvin challenges the dogmas of liberal democracy. A major influence on Peter Thiel and J.D. Vance, he embodies a radical critique of modernity and its egalitarian illusions. Blending political theory with futuristic visions, he is as fascinating as he is unsettling. A conversation.

Interview conducted by Gabriel Piniés.

ÉLÉMENTS: Your concept of the "Cathedral" is very interesting. Could you remind our French readers of its meaning? Do you think that Elon Musk, with his takeover of Twitter and his project for an unbiased artificial intelligence, is trying to build a kind of "anti-university" in opposition to this "Cathedral"?

CURTIS YARVIN: The "Cathedral" refers to our entire intellectual establishment—the academic world, major media—that appears to follow a common ideological and political direction, despite the absence of any apparent central coordination. This party line evolves over time, yet the entire system adheres to it uniformly, as if we were living under a totalitarian regime with a Ministry of Propaganda orchestrating public opinion. And yet, that is not the case.

The Cathedral operates like a singular Church with a single Pope, but when you look more closely, you discover a completely decentralized network of prestigious institutions spread across the globe. How can we explain that Harvard, Yale, Oxford, or the Sorbonne are always aligned with the same ideological stance? There is no organization coordinating them, no party defining this line. And yet, it undeniably exists. The true mystery of the Cathedral lies in this form of invisible yet extraordinarily effective self-coordination.

ÉLÉMENTS: Musk has described wokism as a "woke mind virus." You seem to have influenced this viral perspective. Do you think this "virus" is intrinsic to our modernity, or is it merely an accident of history?

CURTIS YARVIN: For the past 250 years, all major revolutionary ideas in Europe have originated in England and America. Even when some of them passed through Russia, it was only a temporary stop. It would be futile for a Frenchman to deny the influence of English ideas on events like the French Revolution.

But modernity, with its luxury and leisure, weakens societies, making them vulnerable to a kind of intellectual "blight." The "bacteria" could have emerged anywhere, but in reality, it came from England and the United States—historical incubators of this revolutionary and destructive dynamic.

ÉLÉMENTS: The coming decades promise spectacular advances in robotics, AI, and quantum computing. How can we prevent the rise of an authoritarian technological complex that contradicts our fundamental values?

CURTIS YARVIN: The idea that enhancing the state technologically will make it bigger and more intrusive is a fundamental mistake. In fact, the logic works in the opposite direction—at least for an efficient state, which maintains itself through stability and legitimacy rather than mass surveillance.

There are inefficient states, but their ability to cause harm is independent of their technology; they can wreak as much havoc as they wish with nothing more than machetes.

ÉLÉMENTS: One question keeps nagging at me regarding your contractualism. You describe futuristic city-states governed by a CEO or a king, where citizens would enter and exit by contract. Isn’t this a critique of liberalism from within liberalism? Do you think this model can provide people with a sufficiently strong and coherent identity?

CURTIS YARVIN: My early work contains a great deal of classical liberalism, which I would certainly not repudiate. But there is a mysticism surrounding the idea of the state, often tied to a mystique of democracy, which obscures the true nature of the state.

Demystifying this relationship and redefining what it means to be a subject of the state is a priority for me. Take the terms “citizen” and “subject”: to me, the idea of a citizen is an illusion. In reality, we are subjects, and recognizing this could make our relationship with the state more honest and functional.

ÉLÉMENTS: Why?

CURTIS YARVIN: Because the state wields immense power, far above us. The idea that there is some intrinsic quality to being a citizen is more theological than it is a real distinction. You are either free or you are not—there is no such thing as being partially free (x% free). That is simply not given to us.

Take any ordinary French citizen: what real ability does he have to influence the European Commission? None—just as little as he would have had to overthrow Louis XIV under the Ancien Régime. Yet, the European Commission is often presented as if it were anointed with the holy oil of democracy.

Demystifying this is a typically Anglo-Saxon approach, rooted in my intellectual heritage. And in my view, it is the best way to understand reality.

ÉLÉMENTS: But don’t you think that this contractualism, inherited from the Enlightenment, is one of the roots of the universalism that is now destroying us?

CURTIS YARVIN: That’s a good question. I believe it’s possible to overturn the Enlightenment while still recognizing its usefulness. It allows us to pierce through mysteries and demystify illusions—after all, holy oil is just ordinary oil. But once these mysteries have been dispelled, the intellectual tools of the Enlightenment remain relevant.

Look at Joseph de Maistre: in a way, he was a neoreactionary before his time. Trained in Enlightenment principles, he thought using their tools—but it was through them that he realized the Ancien Régime was vastly superior to the Revolution. His great work, Du Pape, is an ultramontane manifesto. Yet traditionalists rooted in the medieval spirit saw him as a man who, despite his ideas, wrote, thought, and breathed like Voltaire, and they struggled to fully trust him.

In a similar way, Mark Twain is the American Voltaire. In his time, Twain was a radical liberal, a bold demystifier. The tragedy is that he never could have imagined that, centuries later, his work would be accused of racism. This perfectly illustrates the limits of the Enlightenment: it provides powerful critical tools, but it is not immune to cultural shifts and changing sensitivities.

ÉLÉMENTS: Don’t you think that this contractualism is at the root of our lack of ethnic consciousness?

CURTIS YARVIN: Yes, but when one door closes, another opens. If the door that has closed is that of a 19th-century mystique of blood and soil, today we have new tools—such as human genetics and a more realistic political science—that seem to tell a similar story. If these modern tools lead us to the same conclusions, aren’t they better suited to our time?

It is possible to rethink these themes using the means of modernity, leveraging its advancements while avoiding the obscurantism of ignoring the impact of Reason. Rather than attempting a return to a premodern way of thinking, where myth remains intact, we can adopt a postmodern approach that illuminates myth with today’s critical tools.

For example, one could certainly imagine an ethno-state founded on Reason, though the level of understanding required might only be accessible to a minority—perhaps 20% of the population—capable of grasping the subtleties of human genetics. But then again, how many people today truly understand Catholicism and its theology? Probably not many more.

That said, beyond human genetics, there are also deeply rooted natural instincts. These instincts, combined with modern tools of Reason, could allow us to revisit ancient ideas with renewed relevance, adapted to our time.

If you go, for example, to the great Burning Man gathering [literally "the burning man," an annual pop-pagan pilgrimage of the new American counterculture, where for nine days participants build a temporary city in the Nevada desert, Ed.]—I’ve been there—it looks like an ethno-state: the sociology of the festival-goers resembles that of a Ku Klux Klan rally.

This happens naturally, through free association, without any contract. There is no one at the entrance of Burning Man, like in South Africa, checking your skin color. There may be Black attendees, but they are very few (between us, only White people are crazy enough for this festival).

So you see, it is possible to arrive at the same result without necessarily repudiating Voltaire.

ÉLÉMENTS: There is a quote from Nietzsche that we really like: The man of the future is the one with the longest memory. What do you think?

CURTIS YARVIN: That’s a very insightful aphorism, which I wasn’t familiar with. In history, we often talk about presentism—this narrow mindset where only the present matters. It’s a very childish attitude.

Today, many people live in a temporal bubble. I recently visited England and asked people if Charles III could actually take back power if he wanted to. In my opinion, the answer is yes. Popular affection for their supposedly democratic—but in reality, bureaucratic—regime is very weak today.

If you go back to the history of the French Revolution, you’ll see the passion with which citizens felt they were in control of their government. They granted immense power to the state, convinced they were the ones wielding it. But once they realized they didn’t actually hold that power, what kept these revolutionary structures alive was simply apathy and conservatism—the idea that nothing better could exist.

In the United States, we have jus soli, which claims that your human rights depend on the GPS coordinates where your mother gave birth. At Harvard, this is taught as self-evident truth, but it’s absurd—it’s just a disguised proxy for race. No one truly believes in it.

We even have a margin of uncertainty of 10 to 20 million people regarding how many actually live in the U.S. And if you ask Americans whether they feel safe walking at night, 40% will say no. If a 19th-century Londoner saw his city today, he would find it dangerous and repulsive.

Understanding the mindset of past eras is essential to properly judging the present.

Curtis Yarvin’s works are available as anthologies, Unqualified Reservations and Gray Mirror, over at Passage Publishing.

Elements magazine - proving again its worth. It’s a pity there’s not more content translated into English.

Illuminating. Thanks!