Armin Mohler on Ernst Jünger's Der Arbeiter

Armin Mohler's foreword to Marcel Decombis' book, Ernst Jünger et la « konservative revolution » (1975)

Marcel Decombis’ book, Ernst Jünger et la « konservative revolution » (1975). Foreword written by Armin Mohler. Available at Éléments.

In the year 1932, Ernst Jünger's book titled Der Arbeiter. Herrschaft und Gestalt ("The Worker. Domination and Form") was published in Hamburg, at the Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt. Immediately, the spiritual elites became aware that this volume of three hundred pages bound in black cloth constituted an extraordinary event. The reaction of Martin Heidegger and Gottfried Benn was typical: for both of them, Der Arbeiter was the book that provided the key to the current situation; for both of them, Jünger remained solely the author of this book, the rest of his work not being taken into account in their eyes. Also significant is the position this book occupies in relation to Jünger's output. It stands as an erratic block, without any connection to what Jünger had written before or what he wrote after, and, to this day, it has remained one of the rare texts by this author that has never been translated, for the good reason that it is basically untranslatable.

Already, towards the end of the 1920s, Ernst Jünger had emerged as the most brilliant writer of the young Right. Since his first book, In Stahlgewittern ("Storm of Steel", 1920), he had evolved with a speed that most of the traditional Right could hardly keep up with. The highly decorated front officer - he had been, along with Rommel, one of the few lieutenants to receive the "Pour le mérite" Order - had started by making a name for himself as the spokesman for the trench generation. But he soon went beyond the naive nationalism of the veteran. At the end of the 1920s, he went through a phase of "Prussian anarchism" which gave us one of his most wonderful books, the first version of Das abenteuerliche Herz ("The Adventurous Heart", 1929). This work, also never translated, bearing the significant subtitle Aufzeichnungen bei Tag und Nacht ("Notes taken by day and night"), differs completely from the book published under the same title in 1938. However, people had barely gotten used to this anarchist and surrealist Jünger when the publication of Der Arbeiter plunged the right into total confusion. The author was now labeled as a "national-Bolshevik", and authors of the traditional Right, like Hans Grimm, felt it necessary to warn against Jünger as a representative of the "leftists of the right". Another spokesperson for this traditional Right, Max Hildebert Boehm, who came from the circle surrounding Moeller van den Bruck, even went so far as to publish a pamphlet against Jünger's book, giving it the revealing title Der Bürger im Kreuzfeuer ("The Bourgeois Under Crossfire", 1933).

Today, with the perspective of time, it becomes evident that Der Arbeiter went far beyond this apparent opposition of the moment, that it surpassed the opposition between "bourgeois" and "worker", as well as that of "right" and "left". Since the "Aufklärung" (German Enlightenment) drew its fatal boundaries, the German spirit has repeatedly strived to overcome the break between the "This side" and the "Beyond", between "Materialism" and "Idealism". Der Arbeiter belongs to this lineage. It is unthinkable without Nietzsche's impulses, although Jünger already stands on ground that Nietzsche had only sensed from afar. The book is also unthinkable without the intellectual stimulation from the philosopher Hugo Fischer (born in 1897), who, at the time Der Arbeiter was written, was Jünger's most important interlocutor and correspondent. Der Arbeiter is more than a philosophy: it is a poetic creation. All the more credit goes to Marcel Decombis for having transposed this untranslatable work into a system of thought comprehensible to the French and which, nevertheless, does not betray the German original. Of course, Decombis knew that an untranslatable residue remains, and that is why he introduced notes into his text that restore key quotations in their original form. These will allow those who master both languages to understand why Der Arbeiter represents for many - and also for the author of these lines - one of the few great books of this century.

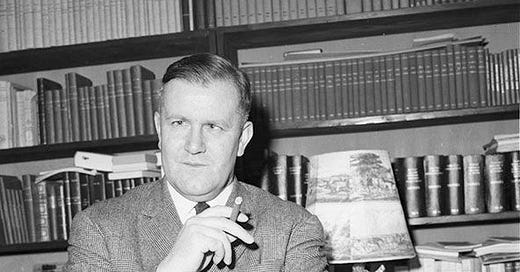

Armin Mohler

Born in Basel in 1920, Doctor of Philosophy, Dr. Armin Mohler was, from 1949 to 1953, Ernst Jünger's private secretary in Ravensburg and Willingen, Germany. A former Paris correspondent for several German newspapers (1953-1961), he has dedicated books to Gaullism, the Fifth Republic (Die fünfte Republik. Was steht hinter de Gaulle? R. Piper & Co., München, 1963) and the French right (Die französische Rechte. Vom Kampf um Frankreichs Ideologienpanzer. Isar Verlag, München, 1958). His other essays have earned him recognition as one of the main spokespersons for German neo-conservatism (Was die Deutschen fürchten, Seewald, Stuttgart, 1965; Vergangenheitsbewältigung, Seewald, Stuttgart, 1968; Sex und Politik, Rombach, Freiburg/Br., 1972; Von rechts gesehen, Seewald, Stuttgart, 1974). His most famous work, on the "conservative revolution" (Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschland 1918-1932, Friedrich Vorwerk, Stuttgart, 1950 and Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, 1972), is considered authoritative worldwide. Addenauer Prize winner in 1967, lecturer at the University of Innsbruck, Dr. Mohler is also director of the Siemens Foundation in Munich. He contributes to Die Welt and the magazine Criticon.