1968 was a year that shook the world to its core. From the streets of Paris to the campuses of the United States, a new generation rose to challenge the systems that had long defined their lives. The youth, disillusioned with the status quo, sparked a fire that threatened to consume the old order, giving birth to what seemed like a new world. But, as history often reveals, the fervor of revolution rarely meets the expectations of those who dream it. Tomislav Sunic’s essay, "1968: The Incisive Year," explores the disillusionment that followed the iconic protests and offers a piercing reflection on how the events of 1968 reshaped not only the world but the very ideals that fueled it. A year of passionate rebellion became a moment of profound realization—an awakening to the complex realities of revolution, identity, and ideological transformation.

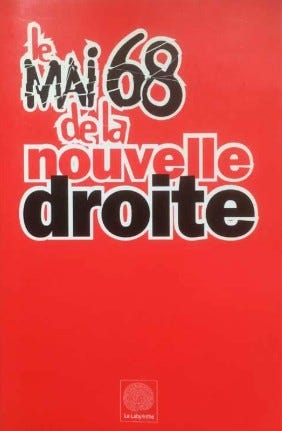

The following essay is an excerpt from the book «Le mai 68 de la nouvelle droite» (TN: May 68 of the New Right), published in 1998.

Translated by Alexander Raynor

The year 1968 stands as a deeply significant and cutting moment in history. It was a year when the world seemed to tear at the seams, and the generational confrontations that had been simmering for years reached a boiling point. Whether viewed as a moment of rebellion or revolution, the events of that year would be etched into the collective memory of the twentieth century. This period witnessed a shift in the cultural and political landscape, affecting Europe, the United States, and many other parts of the world. It was, in essence, a year of seismic change.

For the youth of the time, especially in the West, 1968 symbolized an awakening—an attempt to break free from the norms imposed by previous generations. In the student protests, labor strikes, and societal upheavals, a new sense of political consciousness emerged. The forces that motivated these movements were as much about rejecting the status quo as they were about a search for new ideals and visions for the future.

Yet, as with any great movement, the enthusiasm of youth collided with the reality of political structures and ideologies. The movements of 1968 were not all the same; they were fractured, disillusioned, and eventually co-opted by the very forces they sought to overthrow. But they still represent a moment when the old world seemed on the verge of collapse, replaced by the promise of something new.

For those like me, growing up in Yugoslavia, 1968 was an odd year. We were not directly part of the major Western protests, but we lived through similar tensions. While the student protests in Paris and the United States made headlines, we faced our own version of rebellion, born of the struggle against the ideological constraints placed upon us by the communist regime. Our discontent was not with capitalism, as it was for the students of the West, but with the dogmatic, oppressive nature of the state system under which we lived.

To understand the significance of 1968, we must look at it not just as a singular event but as the culmination of broader historical forces. It was the result of a generation that had grown up in the shadow of two world wars and had inherited a world full of unresolved contradictions. In this sense, 1968 was not an isolated incident, but part of a larger historical trajectory that began with the Great War and continued through the interwar period.

The energy that defined the 1968 protests in the West was something that resonated with youth everywhere, including in places like Yugoslavia, where we felt the urge to question the state and the rigid ideological constraints placed upon us by the communist authorities. We were all part of a generation that had witnessed the dominance of the previous political regimes, but the difference was that, in the West, these movements were pushing for freedom against capitalist systems, while in the communist world, we had a different kind of frustration. We were rebelling against a system that we felt had trapped us in a world of conformity and ideological dogma.

For me, and for many of my peers, the political atmosphere in Yugoslavia during the late 1960s was a peculiar mixture of both repression and a subtle thirst for change. The communist party maintained its strong grip on the political system, but the generational divide was beginning to show. The older generations, shaped by the trauma of war and revolution, continued to support the status quo, while we, the youth, were yearning for new ideas, more freedom, and the possibility of creating a different future.

1968 represented not just the rebellious spirit of youth, but also the internal contradictions of the world that we inhabited. On one hand, there was the desire to tear down the existing structures that seemed to limit our possibilities. On the other, there was a profound uncertainty about what would replace them. The protests in the West, especially in France, were powerful demonstrations of this desire for change, but they were not without their flaws. Despite the passionate protests, many of the movements eventually lost their original revolutionary fervor, becoming entangled in the very systems they had sought to dismantle.

The protests in Paris, for example, were not just about rejecting the authority of the government but were also symbolic of a deeper discontent with the cultural norms of the time. In the streets of the Latin Quarter, students clashed with the police, but what was also at stake was the very way people viewed their place in society. The youth were rejecting traditional values, and in doing so, they created a rupture with the past. However, in hindsight, many of the ideals they fought for seemed superficial. The movement had great energy and passion, but in the end, it lacked a coherent vision for the future. It was a revolt against authority, but without a clear alternative to offer.

In Yugoslavia, we were not as directly involved in the protests, but we felt the reverberations of the upheaval. The youth in our country were also looking for answers to the existential questions that had haunted the previous generation. The ideals of Marxism, which had been the guiding force of the Yugoslav system, seemed increasingly irrelevant to us. The system that had promised equality and justice had instead created a society that was stifled by bureaucracy, inefficiency, and political control. We were not fighting for individual freedoms in the same way the West was, but we were just as disillusioned with the existing system.

As the year 1968 progressed, the atmosphere in both the West and the East became one of anticipation and tension. In the West, the student uprisings were seen as a clear signal of a generation rebelling against its parents' world, a demand for change that echoed in the streets of Paris, Berlin, and Prague. Meanwhile, in Eastern Europe, particularly in Yugoslavia, a quieter form of rebellion was emerging. The idea of revolution was not as evident, but the dissatisfaction was no less intense.

In our country, we were living in the shadow of a political system that claimed to be building socialism, yet was marked by an increasing disconnect between the ruling elites and the everyday lives of the people. For many young people like me, the system felt out of touch with our reality. While the West sought freedom from capitalism, we sought freedom from the suffocating grip of state ideology, bureaucracy, and the pervasive influence of a government that controlled almost every aspect of life.

The discontent among the youth was clear, but it was not accompanied by the same kind of open, public protest that took place in the West. Instead, we found ourselves questioning the very foundations of the system. The political speeches, the endless propaganda about the glories of socialism, and the rigid control over cultural and intellectual life were all things we could not ignore. But at the same time, we knew that to openly challenge the system could have serious consequences. In a way, we were trapped between our desire for change and the very real threat of punishment that loomed over any act of rebellion.

While the youth movements in the West were openly defiant, the discontent in Yugoslavia, and other communist countries, was often more subdued and intellectual. It was expressed in private conversations, in literature, and in art, where we sought to find new ways to express our frustrations. For many of us, the challenge was not simply about rejecting the government, but about rethinking the entire political structure and its underlying ideology. We were searching for something more profound than just a change of leadership or policy; we were questioning the very nature of the system that governed us.

In retrospect, 1968 can be seen as a turning point. It was a year when the young generation, particularly in the West, boldly proclaimed its independence from the previous generation’s ideals. Yet, as time went on, it became clear that the promises of radical change were often empty. The student uprisings and the protests against the establishment were intense, but they failed to produce the fundamental transformations that many had hoped for. Instead, they were co-opted by the very forces they sought to challenge, leading to a situation where many of the revolutionaries of 1968 ended up becoming part of the new political and economic order.

In Yugoslavia, the aftermath of 1968 was marked by a similar disillusionment. The ideological battles that had raged throughout the decade began to dissipate, and the desire for radical change was replaced by a more pragmatic approach to life. The old ideologies that had once promised a new world were beginning to lose their power, and many young people found themselves turning inward, seeking answers not in politics, but in personal freedom and self-exploration.

The protests of 1968, in both the West and the Eastern Bloc, were, in many ways, a manifestation of youthful frustration with a world that seemed stagnant and oppressive. But as the years went by, it became apparent that these movements, for all their passion and energy, lacked the depth of philosophical or political substance to bring about lasting change. In the West, the student uprisings were quickly absorbed by the very system they sought to overthrow, with many of the leaders of the movement eventually finding comfortable places within the neoliberal order they had once opposed. The promises of revolution faded, and in their place emerged a system that was more insidious than anything they had anticipated.

In the East, particularly in Yugoslavia, the situation was no different. The communist government, which had once promised a utopian society built on Marxist principles, was increasingly seen as a force of repression, unable or unwilling to address the fundamental issues that plagued the country. The youth, much like their Western counterparts, began to question the authority of the state and the official ideology, but they did so in more subtle and intellectual ways. The intellectuals and artists were at the forefront of this challenge, but the consequences of open rebellion were far more severe in the East. We did not have the same freedom of speech or expression as in the West, and dissent was often punished harshly.

Looking back, the events of 1968, both in the East and the West, seem like an anomaly. They were a brief moment in time when the old order seemed to be on the brink of collapse, yet the systems in place proved to be more resilient than anyone could have anticipated. What followed was not a revolution, but a series of slow, incremental changes that, over time, reshaped the political landscape. In the West, the values of the 1968 revolution were absorbed into the dominant capitalist framework, while in the East, the communist regimes adapted to new realities, increasingly abandoning their original revolutionary ideals.

For those of us who came of age in 1968, the aftermath of the movement was a lesson in the limitations of ideological purity. It became clear that revolution, as an abstract ideal, could not be achieved through protest alone. The social and political systems we sought to change were too deeply entrenched, and the forces of capitalism and communism were far more adaptable than we had imagined. The true challenge lay not in overthrowing the system but in understanding how to navigate the contradictions that it presented.

The youth of 1968 had a grand vision of overthrowing the old order and creating a new, freer world. However, as the years passed, it became clear that the reality of what followed was far more complicated. The revolution that we had hoped for was not realized in the way we imagined. Instead, what followed was a world shaped by the very systems of power we had once sought to reject. The leaders of the 1968 movements were no longer the fiery revolutionaries calling for radical change; they were now the establishment figures, contributing to the very capitalist and bureaucratic structures they had once condemned.

For us, in Eastern Europe, the aftermath of 1968 was particularly disheartening. Our fight had been different—ours was a rebellion not against capitalism but against the suffocating grip of state socialism. In the West, the youth had been driven by an anger against the capitalist system and the perceived oppression of individual freedoms. In the East, however, the problem was not just economic exploitation but also the loss of personal freedom within a totalitarian regime. We had no illusions about the system in which we lived, but we were left with few alternatives. The ideals of revolution that had been so powerful in our youth gradually faded, and we found ourselves faced with the harsh reality of a world in which power was still firmly held by the same institutions.

Yet, despite all the disillusionment, there was something valuable in the spirit of 1968—a desire for freedom, for change, for a break with the past. This spirit, though often misunderstood or betrayed, continued to resonate in the following decades. Even as the youth movements were co-opted by the systems they sought to challenge, the ideas that emerged from 1968—of freedom, individuality, and resistance to authority—continued to influence the course of history.

In the years following 1968, many of the ideals and aspirations of the movement were absorbed into the mainstream. The political landscape shifted, and the social revolutions of the time—such as the rise of feminism, environmentalism, and the expansion of civil rights—found their place in the changing world. However, the radical edge that defined the movement in 1968 was dulled by time. The revolutionaries of that era were no longer speaking of overthrowing the system but were instead working within it to push for reforms. The passion and idealism of youth were replaced by the pragmatism of adulthood.

In the end, the lessons of 1968 are not just about the failure of revolution but about the way in which ideas are absorbed and transformed over time. The dreams of radical change may not have been fully realized, but they left an indelible mark on the world. As the years pass, we are left to reflect on what might have been and on the way in which the ideals of 1968 continue to shape the world we live in today. The spirit of rebellion and the desire for change that characterized that moment in history may have been co-opted, but it is not gone. It lives on in the struggle for a better, more just world.

Impactful year, but the essay itself tells very little - it ends up repeating itself over and over, contrasting East and West, and ending with a trite "it was all absorbed in the end".